Android Telephony Basics

Written on June 18, 2018 by javelinanddart

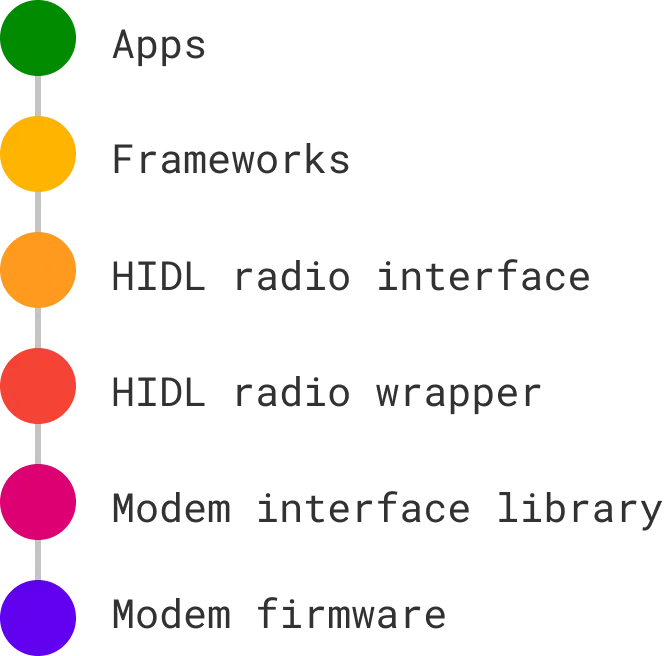

The Android Telephony stack is complicated and contains many parts, each of which can be more or less grouped into the categories pictured below.

Everything below the HIDL Radio Interface is generally proprietary, and may or may not work out of the box on LineageOS. This post will be primarily focused on how the HIDL Radio Wrapper (more commonly known as “libril”) communicates with the Telephony Frameworks. The communication of the HIDL wrapper to the HIDL interface will be covered in more depth in a future post.

Glossary

- Command: A request from frameworks to modem to perform a task, or return data required by userspace

- Request: See Command

- Response: Information from the modem to frameworks in response to a request being sent

- Indication: Information from the modem to the frameworks as a result of an event occurring

- Solicited Response: Legacy name for Response

- Unsolicited Response: Legacy name for Indication

- Unsol: Short for unsolicited response

- DSDA: Short for Dual SIM Dual Active, a type of Multi-SIM device in which two discrete modems are present, and two subscriptions can be active at the same time

- DSDS: Short for Dual SIM Dual Standby, a type of Multi-SIM device in which one modem handles two SIM slots, and only one subscription can be active at any given time

- IMS: Short for IP Multimedia Subsystem, used as an umbrella term for features such as VoLTE and WFC (VoWiFi) in Android

- VoLTE: Short for Voice over LTE, standard for transmitting phone calls over LTE networks

- VoWiFi: Short for Voice over WiFi, alternate name for WFC

- WFC: Short for WiFi Calling

- RIL: Short for Radio Interface Layer, generally used to refer to the modem interface library or libril, sometimes used to refer to any part or the whole of the Telephony stack

What is Telephony?

Telephony is an umbrella term used to describe nearly everything relating to communication with a cellular network.

Basic Overview

Put simply, the communication from the modem to the frameworks is just data serialization. Data is sent between the frameworks and the modem, marked by a special identifier code, and structured in a special format understood by all parts of the stack. Specifically, there is one way to send data to the modem, and two ways to receive data from the modem. Android uses what are called “requests” to send data to the modem. This is generally to perform a task (e.g. dialing a call), to receive information (e.g. getting the SIM card status), or to send information (e.g. sending a SIM PIN that has been entered). When receiving data from the modem, there are two different types of responses: solicited and unsolicited. Solicited responses are a “reaction” to a request that Android sends. In the example of a dial request, a dial response is returned, containing information used by Android to determine what to do next. Unsolicited responses are a “reaction” to an event that Android should be aware of. One such example is network time updates, so that in the event of a date, time, timezone, or daylight saving time change, Android is aware of it without having to explicitly poll for such information. An enumeration of the names and identification numbers of AOSP’s requests and responses can be found in the RILConstants class, of which a current revision is hyperlinked.

OEM Additions

Most OEMs extend AOSP’s existing commands and responses by adding their own for extra information, or extra functionality. Generally, these are of no consequence for LineageOS, unless the OEM has used the numbers or renumbered one or several of AOSP’s requests or unsols. This is important because Android may become confused after receiving improper information, may never receive the information at all, or the modem library will be confused after receiving improper information. One such example is on the Qualcomm Samsung Galaxy Note 3, where the unsol code for UNSOL_ON_SS did not line up between AOSP’s implementation and Samsung’s implementation, and as a result, Android never received the information. Nowadays, most OEMs offset all of their custom response and command codes from AOSP’s by arbitrary numbers. Samsung, for example, starts numbering their custom requests at 10001, and their custom unsols at 11000 to avoid conflicting with AOSP, who starts numbering requests at 1 and unsols at 1000. Some OEMs (e.g. OnePlus), however, play a dangerous game of not offsetting their additions. While these are not of relevance while the device is still maintained by the OEM, on Android versions beyond OEM support these previously unused requests and unsols could suddenly become used, causing crashes, confusion, and all around unhappiness.

Reversing OEM Additions

Documenting OEM Requests and Unsols

Generally, OEMs add their custom requests and unsols to the requestToString and responseToString methods in the telephony frameworks. As a result, OEM additions can be obtained by running a java decompiler (jadx works particularly well) on a deodexed telephony-common.jar from a stock image of the device, and then comparing these methods to the AOSP release corresponding to the Android version of the stock image from which the telephony-common jar is being obtained. On the aforementioned Galaxy Note 3, for example, comparing requestToString yielded several requests that did not exist in AOSP, and comparing responseToString yielded many additional unsols not contained in AOSP. The notable exception to Samsung’s additions not being in AOSP, as noted previously, was the addition of unsol 11055, UNSOL_ON_SS, which was present in AOSP as 1043. Examining these methods can provide an abundance of information on how requests and unsols are handled by the OEM.

Reversing OEM libril changes

Following the process outlined in the previous section to compare the stock telephony frameworks to AOSP, OEM changes to libril can sometimes be similarly located. Generally, changes in data structures between AOSP’s telephony-common implementation and the OEM’s implementation are good indicators of where the OEM modified the libril source. RIL.java is a good point of comparison for all devices, and for devices with OEM releases of Oreo or beyond, RadioIndication.java and RadioResponse.java are as well. Making corresponding changes to the data structures in libril is a good way to start reversing the OEM’s libril additions. On the aforementioned Galaxy Note 3, comparing the responseIccCardStatus method from Samsung to AOSP successfully revealed Samsung’s changes to the RIL_AppStatus struct in AOSP. Unfortunately, this isn’t always the case. Comparing the responseCallList methods from Samsung to AOSP yielded the additional call_id and call_details fields; however the placement of the call_details fields differ between the struct and the RIL class. In these instances, the next step is compiling a libril from a comparable AOSP or CAF release to the OEM release, and comparing the binary files, which will be covered in a future post.

Additional notes

Multi-SIM Devices

In the past few years, multi-SIM devices have become increasingly common. Generally speaking, most of these devices have 2 SIM slots, and can be separated into two different categories: DSDA and DSDS. DSDA is the less common of the two, as it requires additional modem hardware, which costs more for the OEM, and comes with a higher power cost. The advantage to DSDA, however, is that multiple SIMs can be active at the same time. DSDS is more common, as all it requires is an additional SIM slot. The downside, of course, is that only one SIM can be active at a time. Both have been supported in Android for the past few years, and should more or less just work after the device tree is appropriately configured.

Telephony Extensions

telephony-ext

Qualcomm provides an extended telephony interface that is used in LineageOS for manual SIM provisioning (manually enabling and disabling SIM cards). For recent Qualcomm devices, this is provided by the qti-telephony-common.jar, which also extends various other Telephony components provided in telephony-common.jar. For other devices, an opensource reimplementation exists, although it is not quite as robust as Qualcomm’s implementation.

IMS

IMS features in Android more or less only work for recent Qualcomm devices at the time of writing, due to several changes in implementation per Android version, and lack of a standardized interface between the telephony frameworks and proprietary components. While IMS features themselves are standardized, the software implementations of them unfortunately are not.